The Blog Revisited, 2025.

It’s been a dozen years or so since I began this blog. I’ve been fortunate to work with many thoughtful customers over twenty-five years, through a wide range of project scales, and budgets. Each project is unique, yet themes and patterns emerge, hence these musings. Recently we’ve rebuilt the website, so I’ve taken the opportunity…

Architecture 101: Part 1

Architecture is a rich endeavor bringing together the many disciplines of history, philosophy, society, geometry, structure, art, craft, function, shelter, and having an enduring presence over time. As a functional art it appeals to both our logical and intuitive natures. We all share the desire to determine our own environment, as well as possess some…

Architecture 101: Part 2

When following historic types, home design appears to be a simple matter of copying model plans. The tradition of pattern books once informed much of the house carpentry in this country, and today the majority of houses built are still based on stock plans. Even here a worldview applies, which could be on the order…

Architecture 101: Part 3

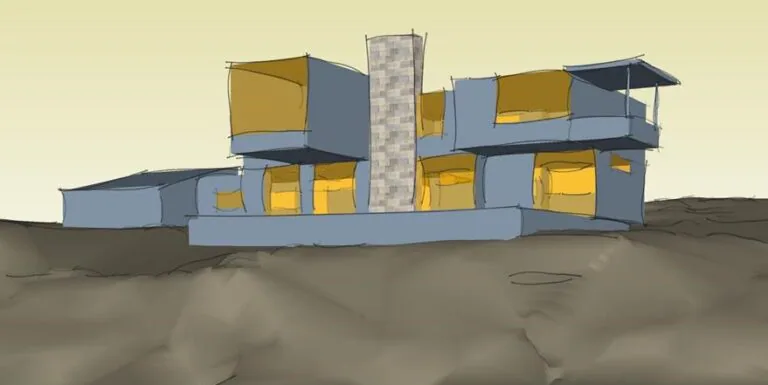

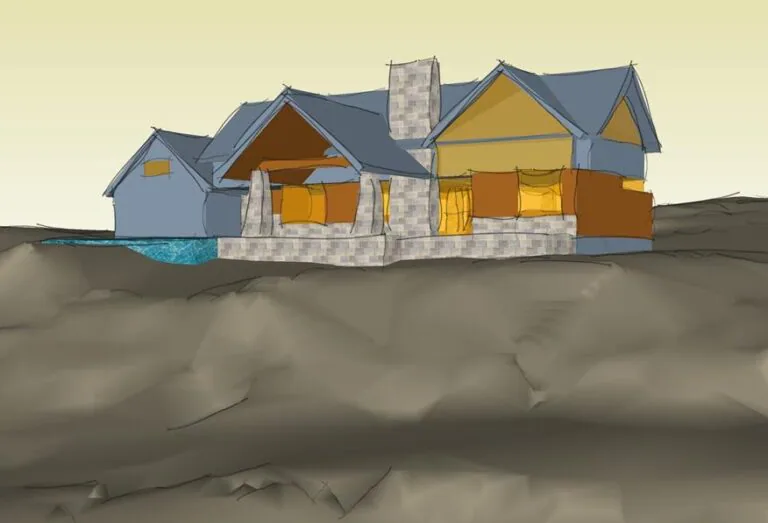

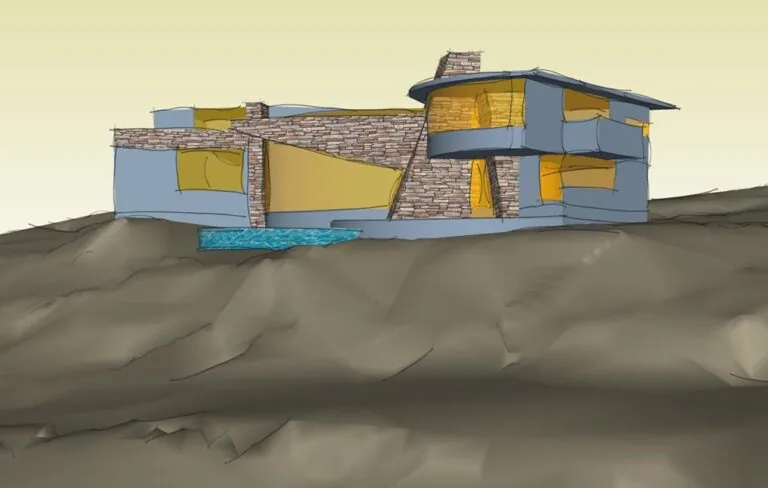

Prior to construction, there are three main influences on home design: the owner(the customer and their budget), the site, and the designer. Change one and the results can be quite different. I am of a practical nature and I like projects to move along the design path without too many detours. We generally start with…

Degree of Difficulty: Part 1

Back in Canada, I worked for an Architect who once likened the practice of Architecture to Olympic figure skating. There is technical skill, finesse, creative interpretation, performance, competition, and success is in part a judgment call. In scoring one looks at all of those elements and judges not only the execution but the degree of…

Degree of Difficulty: Part 2

One of the common questions during the design process is naturally, ‘How much will it cost?’Custom home design is by its very nature, specific. We can offer ballpark figures based on previous projects, and cost-per-square-foot benchmarks. Site work-driveway, septic, well, landscaping is often estimated separately. This applies to ancillary spaces as well-basements, attics, garages, porches…

Degree of Difficulty: Part 3

Architecture can be thought of as a hierarchy of layers. It starts with purpose and space, followed by structure, systems and surface. If we get the bones right, the other layers fall into place more easily. Those layers can also blur together and change places. A project might be driven by structure, or surface, or…

Builders and Managers: Part 1

Hiring a good contractor is essential to a successful project. It is a role that requires a range of skills. I’ve done it myself, I’ve been on the other side as a customer, and I work on the third side as an Architect. With the type of work we do, I find that there are…

Builders and Managers: Part 2

Builders usually work on one or two jobs at a time. They might have a partner, or a family member, or several employees/journeyman that they work with regularly. They fold all the work of management into their day, which often extends into evenings and weekends. They are intimately involved in the carpentry work, and oversee…

Builders and Managers: Part 3

Due to my experience in construction, I am sometimes asked if I’ll manage a home building project. I have done it in the past, but find that it is a tough balancing act. I believe it’s important for a manager to oversee all the trades, coordinate their interaction, and be intimately involved and responsible for…

To Bid or Not to Bid: Part 1

We are all are used to making cost comparisons while shopping, so it’s natural to think of home construction in terms of a competitive bid. The difference in custom home building is that an estimate is based not only on a product, but also upon a service. What assumptions have been made within a given…

To Bid or Not to Bid: Part 2

As a small practice we strive to keep services and documents to a reasonable level. There should be enough information at a given stage to allow estimates within a cost range, and allow for a bid process should that be desired. Yet good residential contractors are often busy without resorting to the time-consuming and uncertain…