Our previous blog outlined the goals and strategies of Passive House (PH) Certification. Born in the generally mild climate of Germany, this rigorous energy use target has been more difficult to achieve across the various climate zones of the United States. Here in the northeast, the wisdom of a one-size-fits-all standard has been questioned. Recently, one North American PH provider has been working to establish a set of zones, with consumption targets dialed to regional climate conditions. For those interested in a more in-depth look at this topic, I suggest an article by Martin Holliday at Green Building Advisor from 2015: Redefining Passivhaus https://www.greenbuildingadvisor.com/article/redefining-passivhaus

At a less intensive level, there are also basic rules of thumb that can be used to reap many of the same benefits of Passive House, without the energy modeling and certification required. Coined the Pretty Good House (PGH), it takes a more humble approach, and recognizes the law of diminishing returns when it comes to investment in energy performance upgrades. In our Climate Zone 5, the basic PGH insulation strategy is: 5-10-20-40-60. That’s R5 for windows, R10 below the slab, R20 for the foundation walls, R40 exterior walls, and R60 for the roof. For more information on this approach, seen another article by Holliday from 2014: Martin’s Pretty Good House Manifesto https://www.greenbuildingadvisor.com/article/martins-pretty-good-house-manifesto

In the evolution of energy performance criteria, the two have learned from each other. Passivehaus was initially inspired by the North American passive solar and super-insulated houses of the 1970s. In turn, Pretty Good House has benefited from the pursuit of efficiency in Europe that has resulted in vast improvements to heating, cooling, and fresh air technology; as well as triple-glazed windows, and other construction assemblies. Those in turn have been imported back to North America. Although I get excited about the super-efficient potential of Passive House, my customers tend toward a less intensive approach. A good balance of investment, with comfort and efficiency, is the approach that Pretty Good House can provide.

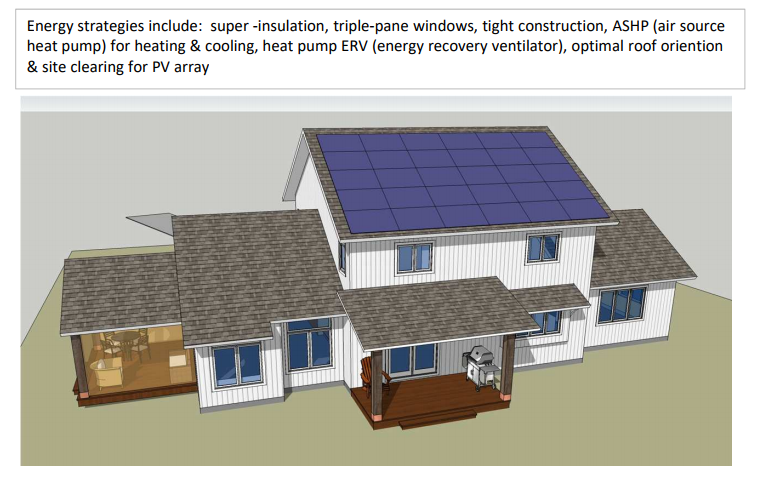

There is another aspect to home energy use and reducing dependence on fossil fuels, that being active Solar, Photovoltaic (PV) systems. Although larger community arrays are more efficient, there is still a place at this time for individual home PV systems. The advent of inexpensive solar panels introduces a cost/benefit curve that brings a Zero Net Energy Home into the conversation. The strategy here is to consider a reasonably sized PV array that will produce energy over the year, sent back to the grid, to offset the entire energy use for a home over the same period. It still requires a high level of integrated design, including, high performance insulation, windows, mechanical systems, and air-tightness. But the focus is shifted from the somewhat arbitrary target of Passive House, to the specific target of Zero Net Energy use on site.

In considering these approaches, as with all the many decisions in designing and building a home, more goes into it than just the cost. There is a value proposition in choosing all-electric, and even creating energy on site. Hybrid systems can also be a very good choice. These values also apply to choosing materials and methods that have less impact on the environment. Embodied energy considers the life-cycle cost of extraction, production, and transportation. We aim to keep things pretty simple when we can, specifying materials that are mostly within the reach of the local lumber yard. There are exceptions, for unique materials and newer products. One such product is European triple-glazed windows that are still superior and often less costly than their North American counterparts. While energy use is important, I think of it in terms of the common sense of conservation and right-sizing. In addition, I do have a preference for natural and local materials, such as stone, wood, metal, glass, and ceramics—materials, and strategies, that connect a project to the earth, and to the locus of a home.